Sandy and I have decided to take off the month of August regarding the creation of two new blogs. We will switch our focus this month to finishing the second volume of the German occupation of Paris (Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). We’re so close to wrapping up the new book that I am going to put blinders on and focus one hundred percent on completing it.

In the meantime, we are “repurposing” two of our prior blogs for August. Two weeks ago, we expanded and reprinted the 2017 blog, The Sussex Plan and a Very Brave Woman (click here to read the blog). Today, we are presenting a blog that was published in 2019. Over the years, we have received many e-mails from people who knew Suzanne’s children, Bazou and Pilette. It was very interesting (and amazing) to hear their stories.

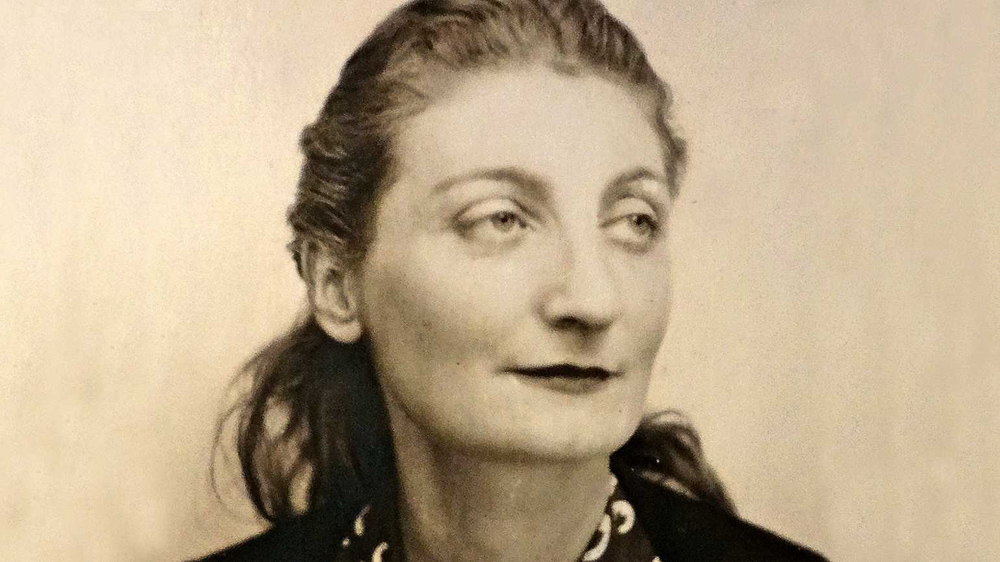

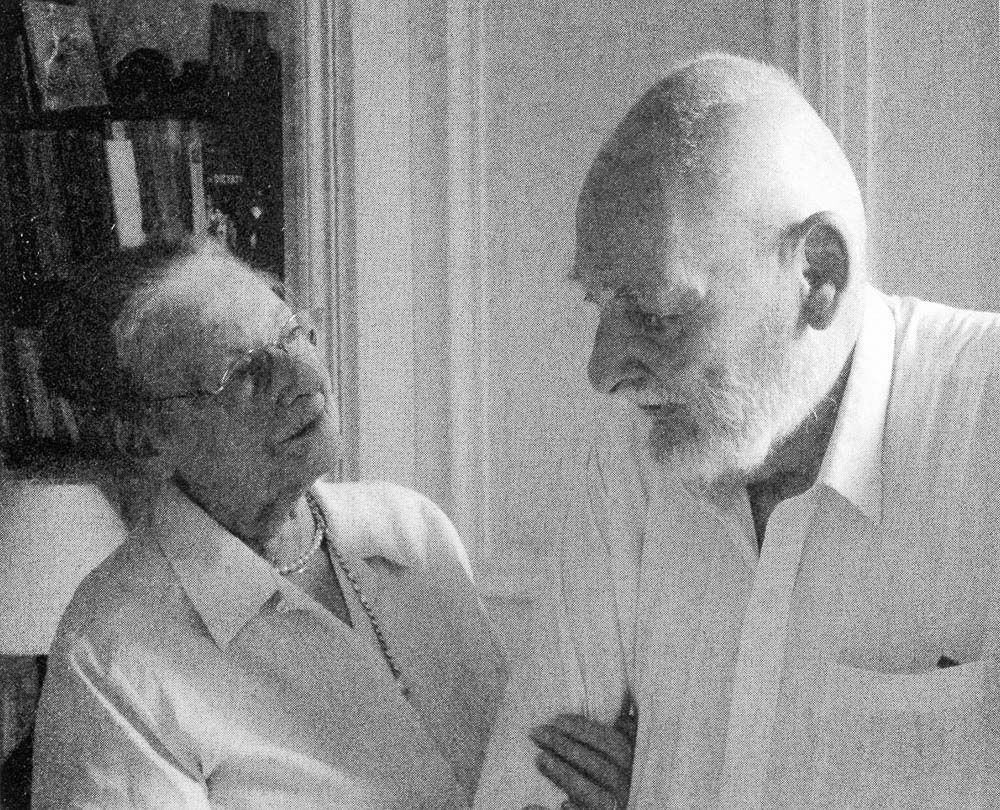

Do you ever wonder how rather obscure stories are resurrected from history’s dust bins? In the case of today’s blog, we have Anne Nelson to thank for uncovering the story of Suzanne Spaak’s resistance activities. Anne is the author of Suzanne’s Children (refer to the recommended reading section at the end of this blog for a link to her book). Anne came across Suzanne while researching her excellent book, Red Orchestra (again, refer to the recommended reading section). A haunting photo of Suzanne found in Leopold Trepper’s memoirs piqued Anne’s interest and initiated her nine-year journey. She was able to locate Suzanne’s daughter, Pilette, in Maryland and a series of three dozen interviews spread out over seven years formed the backbone of Anne’s research. There isn’t much out there regarding Suzanne’s story, so we owe many thanks to Anne for finding and “bird-dogging” the facts surrounding Suzanne’s activities. I’m quite sure she went down many rabbit holes while researching and writing the book. I have read both books and I look forward to Anne’s next book.

I briefly introduced you to Suzanne Spaak in March (The French Anne Frank; click here to read). She and Hélène Berr worked together to save the lives of hundreds of Jewish children. Like most of the résistants during the Occupation, Suzanne and Hélène did what they thought was the right thing to do. As Suzanne told people, “Something must be done.”

Did You Know?

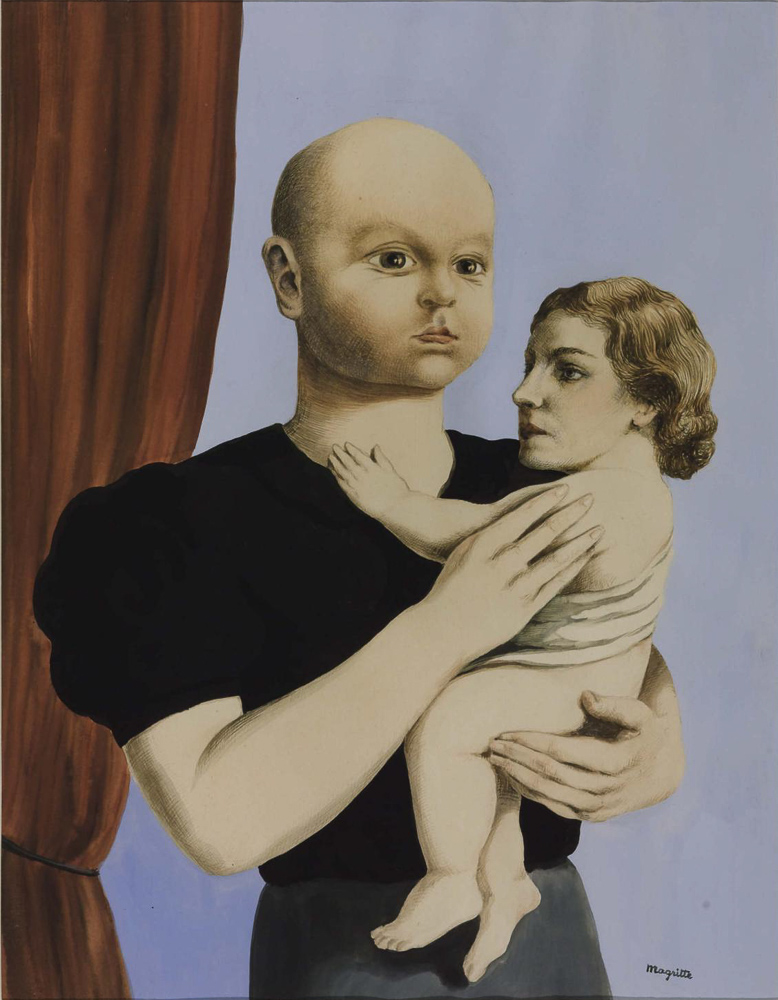

Did you know that the international art world was undergoing new movements during the interwar period (1918–1939)? Picasso, Dalí, and Magritte would each create styles of painting that today we call cubist and surrealism, among others. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Hitler (a frustrated artist in his youth), declared the work of these artists along with dozens more (including many German artists) as degenerate. René Magritte (1898-1967) was a starving Belgian artist whom Claude Spaak befriended while artistic director of the Brussels Palais des Beaux-Arts. At the time, Magritte supported himself by designing wallpaper and sheet music. Spaak began suggesting topics and themes for Magritte to paint. Soon, the Spaak family’s walls were covered with surrealistic images, the likes of which no one had ever seen before. By 1936, Claude convinced his friend to paint family portraits. Probably the most disturbing was L’Esprit de Géométrie, or “Spirit of Geometry.” It is a creepy painting of a mother holding an infant. The problem: the head of the mother was Claude’s four-year-old son, Bazou and the infant’s head was Claude’s wife, Suzanne ⏤ Dalí would be proud. In 1937, Claude moved his family to Paris, but Magritte remained in Belgium where he continued to struggle. At one point, Magritte requested stipends from his patrons. Only Suzanne Spaak stepped up to the plate with a monthly stipend in exchange for paintings. The Spaaks would go on to collect forty-four paintings by Magritte. Five days after the Nazis invaded Belgium, Magritte fled to France where he immediately went to the Spaak’s country home. He requested to “borrow back” several paintings hanging on their wall. When Magritte left for Paris, he was carrying with him a dozen paintings. Magritte had been introduced to an American art collector to whom he would sell his “borrowed” paintings. The collector’s name was Peggy Guggenheim and the Spaak family’s paintings ultimately ended up hanging in her museum.

Let’s Meet Suzanne Spaak

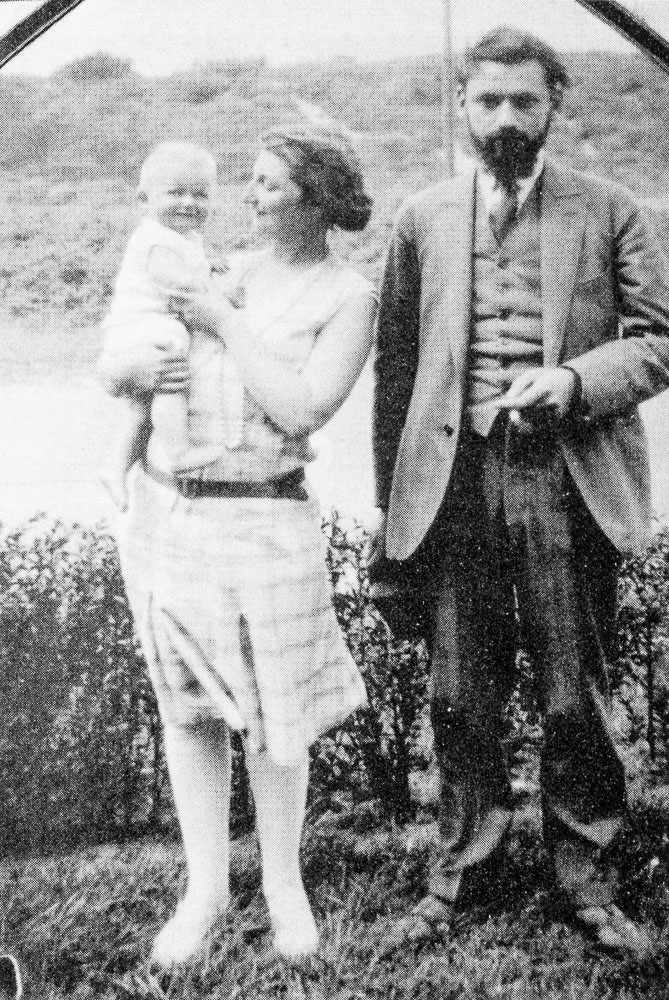

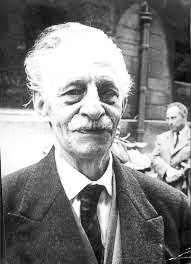

Suzanne Lorge Spaak (1905-1944) or “Suzette” as her family and friends called her, was born into an affluent Belgian family. Her father was a prominent banker and she married Claude Spaak (1904-1990) in 1925. Claude’s family included his brothers Paul-Henri (1899−1972) who became a well-known Belgian politician (prime minister and foreign minister among other positions) and Charles, a famous movie script writer. Suzanne and Claude had two children: Lucie (“Pilette”) and Paul-Louis (“Bazou”) but life together as husband and wife was not happy.

Claude was a philandering spouse with a terrible temper and Suzanne was aware of his escapades but because of the potential negative publicity affecting the two prominent families, divorce was not an option. Instead, Suzanne asked her good friend, Ruth, to become Claude’s mistress (at least she would know where her husband was). By 1937, Claude decided being an art curator wasn’t fun and he began to write plays. After several were picked up by Paris theater producers, Claude moved his family to Paris ⏤ all financed by Suzanne’s dowry and inheritance.

Pre-War Paris Politics

During the inter-war period (i.e., the years between the first and second world War), Paris was politically divided between the “Left” and “Right.” Lining up on the Left were the Socialists, Communists, and the trade unions. Supporters of the Right were monarchists, fascists, right-wing, and generally, antisemitic. The idea of being a “capitalist” was destroyed after the Great Depression worked its way across the Atlantic. France’s government, the Third Republic (1870-1940), was considered to be corrupt and it was eventually dissolved and replaced with the Nazi collaborationist government located in Vichy, France.

Suzanne began her social work while living in Brussels and in 1932, joined the World Committee of Women Against War and Fascism. She supported the Republican forces during the Spanish Civil War.

The Occupation

Between 1880 and 1925, three and a half million Jews left Central and Eastern Europe. Two and a half million emigrated to the United States but in 1924, America closed its doors. France became the number one destination for future Jewish immigrants. By 1939, there were 150,000 Jews living in Paris of which 90,000 were foreign-born. The majority of them settled into the Marais, Belleville, and Montmartre neighborhoods. After the Nazis invaded France, very few French Jews left the country. Jews believed Vichy would protect them from the Nazis because they were born in France or carried French citizenship and fought for France in World War I. Unfortunately for them, the collaborative Vichy government was filled with right-wing politicians and bureaucrats ⏤ most of whom were antisemitic.

During the summer of 1941, the Germans invaded the Soviet Union and Stalin urged all Communists to rise up against the Nazis in the occupied countries. Initially, the majority of the French resistance movement was driven by Communists and in particular, foreign-born Communist Jews.

During this summer, Claude and Suzanne moved the family into an apartment in the Palais Royal. One of their neighbors was Colette (author of Gigi and well-known French celebrity) and the Spaaks began to socialize with the intellectual elite of Paris such as Jean Cocteau.

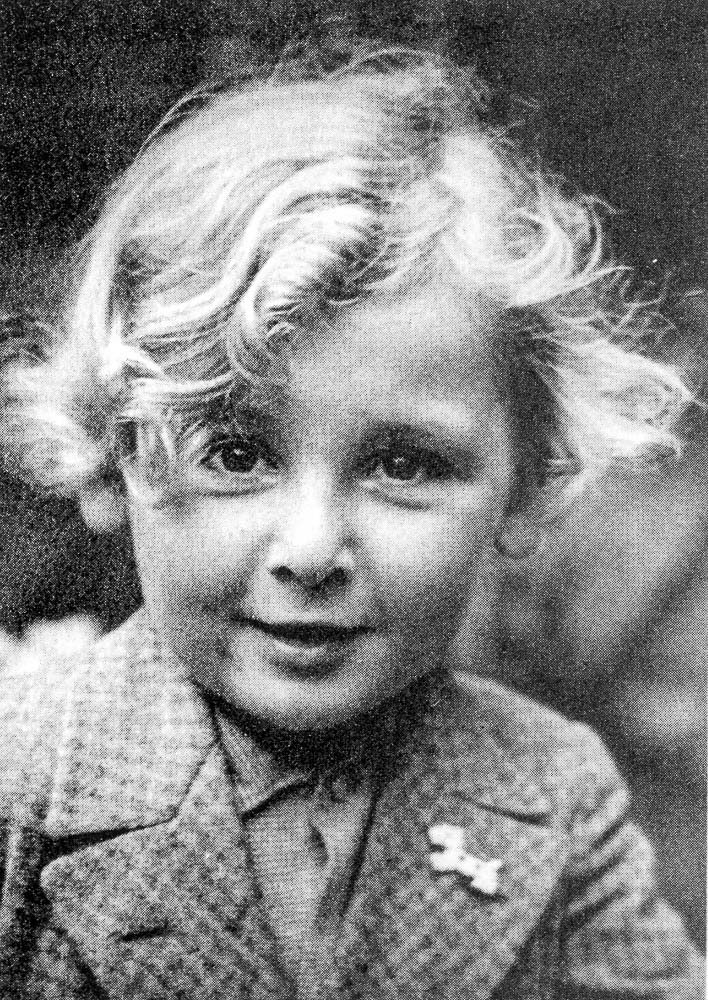

In May 1941, the first major round-up of Jews in Paris took place when 3,800 men were arrested and sent to detention camps. Suzanne joined the Solidarité resistance movement founded in November 1940 by Polish Jews. It was commonly known as the MOI, or Main d’œvre immigrée. Initially, Suzanne was not trusted but very quickly, the MOI saw she was a dedicated résistant and more importantly, she was Catholic, pretty, and socially connected. It meant Suzanne could move around Paris and France pretty much as she wished. She became an important member of this Jewish resistance movement. Beginning with her involvement with the MOI, Suzanne’s children would assist their mother with her resistance activities ⏤ Pilette forged documents and Bazou was a courier.

During the winter of 1941, Suzanne joined another resistance movement called the National Movement Against Racism, or MNCR. It was founded to oppose the “racial” laws imposed for the purpose of harming Jews. Unlike most other resistance networks or organizations, the MNCR operated across all political and religious lines. Suzanne was initially used as a courier and by 1942, she was working on their clandestine newspaper, J’Accuse (its editor, Mounie Nadler, was eventually executed at Fort du Mont-Valérien).

After the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, the Nazis began their systemic murder of Jews. On 16/17 July 1942, the French police in Paris rounded up more than 13,000 Jews (the Nazis had demanded 22,000) of which 4,000 were children. They were sent to detention and transit camps such as Drancy and from there, put on train convoys to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau (Click here to read the blog, The Roundup and the Cycling Arena). As rumors spread through the Jewish community about the pending roundup, Suzanne distributed leaflets warning the residents in the Jewish neighborhoods. After the roundup and knowing 31% of the arrested were children, Suzanne said, “Something must be done.”

Union Generale des Israelites de France (UGIF)

In November 1941, all Jewish charity organizations were consolidated into the UGIF. The Nazis used the UGIF in their efforts to identify Jews, where they lived, and to control the Jewish community. All Jews were required to register with the UGIF and pay dues. One of the UGIF divisions was the orphanage which cared for the children whose parents had been deported. The Nazis did not require children under the age of sixteen to be arrested or deported. However, Vichy (and Pierre Laval) finally ordered Jewish children to be deported.

Rescue: Kidnapping the Children

Shortly after the Grand Roundup of July 1942, Suzanne began visiting Catholic priests, bishops, and even the Cardinal of Paris. She pleaded for the lives of the children, and it resulted in letters sent to Pétain (president of Vichy), sermons about what was going on, and Catholics sheltering Jewish children. The MNCR formed a committee to save as many children as possible from deportation. Suzanne was one of the committee’s founders.

By early February 1943, French police began going around to the Paris UGIF orphanages and arresting children. It seems there weren’t enough adults to fill the deportation convoy quotas demanded by the Germans. Suzanne quickly developed a plan to save the children.

Suzanne began to recruit Catholic women to impersonate family members of the orphaned children staying at the UGIF facilities. The children were allowed to go on walks once a week with someone who was a family member. She knew that once out of the orphanage, the children would need to be fed, clothed, and sheltered. So, Suzanne enlisted the aid of the pastor of a local Protestant church. Pastor Paul Vergara and his wife were active in the Oratoire du Louvre, a Protestant resistant network. Marcelle Vergara and a social worker, Marcelle Guillemot, ran the soup kitchen in the church basement and provided the first destination point for the rescued children. After that, they would be placed in safe homes around the countryside which Suzanne had earlier identified and made arrangements.

Suzanne recruited forty women: twenty-five Protestants and fifteen Jewish. On the morning of 15 February, Suzanne and Pilette met up with the forty women and one group went to the UGIF orphanage at 16, rue Lamarck while another group went on to another UGIF facility at 9, rue Guy Patin. (Both of these buildings are stops in first volume of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?) Each woman identified themselves as a family member and took a child (or two or three) out for their “walk.” The operation was a success and it is generally acknowledged that sixty-three children were saved. The Germans learned about Suzanne’s involvement and they eventually caught up to her but for a different reason.

Arrest

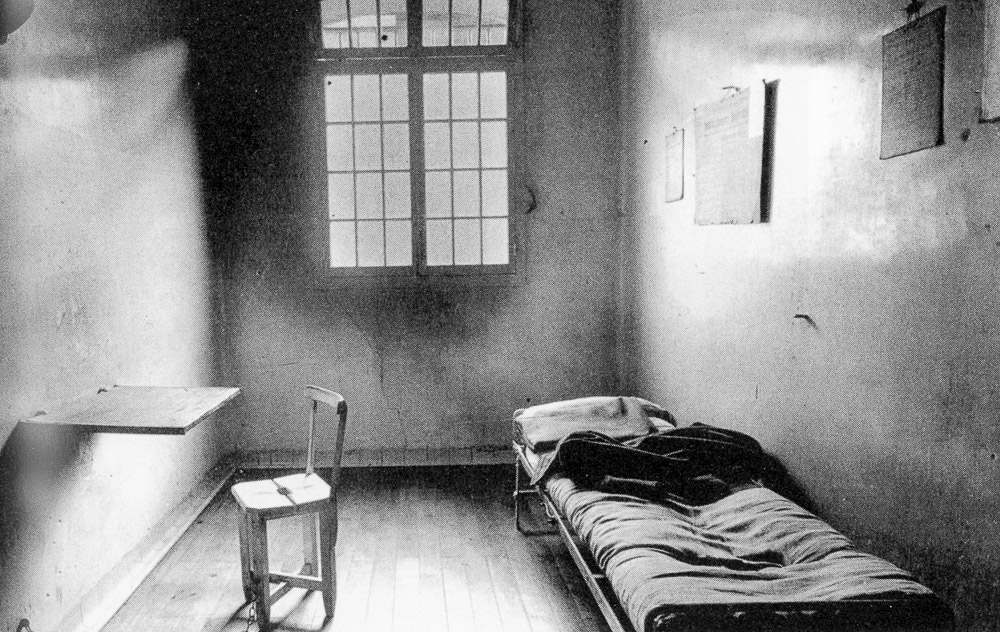

Suzanne became involved with Leopold Trepper and his resistance network, The Red Orchestra (Click here to read the blog, Die Rote Kapelle). The Gestapo had infiltrated the network and had a list of Trepper’s agents, including Suzanne. She and the children fled to Brussels in mid-October 1943. On 24 October, the Gestapo visited Suzanne’s mother’s house (coincidentally, the house was across the street from Gestapo headquarters) and demanded to speak with Suzanne. She was not there but shortly afterwards, Suzanne went into hiding in the Ardennes. She was ultimately betrayed by a friend and on 10 November, Suzanne was arrested by the Gestapo. Put on trial in a Luftwaffe court in January 1944, Suzanne was found guilty and sentenced to death. She was transferred to Fresnes prison where one of her neighbors in the cell block was Geneviève de Gaulle, the general’s niece. (Geneviève survived the war after being deported to KZ Ravensbrück.)

Suzanne began her long wait.

Execution

By the beginning of August 1944, the Allies had broken out of Normandy and were on their way towards Berlin. The Germans in Paris were preparing for their evacuation from the city. It was chaos during those final days. The Nazis were destroying documents, setting explosives around the city, fighting the résistants and Paris citizens in the streets, frantically looting whatever they could send back to Germany, and deporting as many Jews as they could in the final convoys leaving Paris. The Gestapo and the SS were also making sure they didn’t leave any prisoners in the prisons.

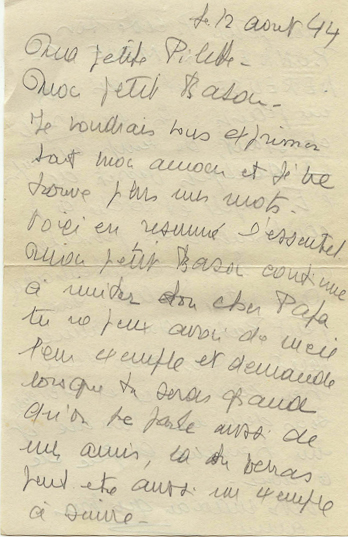

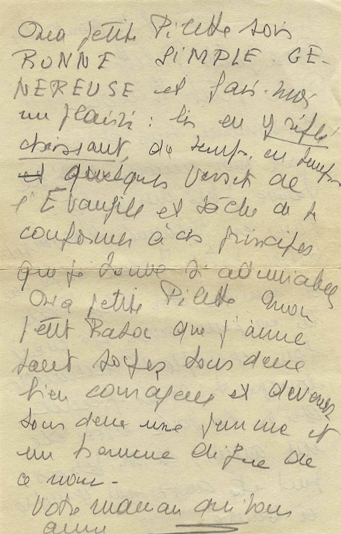

On the morning of 12 August 1944, Suzanne sat down in her cell and wrote a long letter to her children. Shortly after finishing the letter, Suzanne and one other prisoner were taken into the prison courtyard, told to kneel, and shot in the back of the neck.

There is some historical speculation that Suzanne had received a pardon from Berlin, but the paperwork had been lost or overlooked during those last days of the Occupation.

Thirteen days later, Paris was liberated.

Post-War

While Suzanne sat in jail, Claude and Ruth hid out in silence. After the war, they were married, and Claude destroyed all evidence of his marriage to Suzanne. He never talked about Suzanne and the children didn’t learn where their mother was buried until 1956. Claude and Ruth lived a life of luxury financed by Suzanne’s estate. Whenever they needed money, he would sell a Magritte painting.

When Bazou was a teenager, Claude said to him, “I really don’t know what I would have done if your mother had come back.” Bazou never forgave his father for that remark.

Approximately 11,000 children were deported to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau (representing 15% of the French Jews deported). Rescue networks like the one Suzanne ran saved more than one thousand children from being deported.

Humanitarian and “Righteous Among Nations”

When we speak today of a “resistant,” we use this term to classify all of the men and women who fought the Nazis in their respective occupied countries. If Suzanne Spaak had survived the war, her friends said she would have preferred to be labeled under a different term: HUMANITARIAN.

On 21 April 1985, Suzanne was recognized by Yad Vashem on behalf of the State of Israel and the Jewish people as “Righteous Among the Nations.” It is an honor bestowed upon non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. There are four basic conditions someone has to meet to be considered. One of the four criteria is that the motivation to assist was not driven by personal gain.

Suzanne Spaak’s motivation was her love of children.

Next Blog: “Avenue Boch”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Nelson, Anne. Suzanne’s Children: A Daring Rescue in Nazi Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Nelson, Anne. Red Orchestra. New York: Random House, 2009.

Paquet, Marcel. Magritte. London: Taschen, 2015.

Spaak, Paul-Henri. The Continuing Battle: Memoirs of a European. UK: Littlehampton Book Services Ltd., 1971.

Trepper, Leopold. The Great Game: Memoirs of a Master Spy. London: Michael Joseph Ltd, 1977.

Ms. Nelson’s books are excellent for those of you who want to expand your knowledge about Suzanne, the plight of Jewish children in occupied Paris, and the resistance efforts of the Red Orchestra and Leopold Trepper.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are working on finishing the second volume of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi-Occupied Paris (1940−1944) Roundups & Executions.

Thanks to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

We look forward to hearing from you and appreciate those of you who, over the years, have contacted us.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross